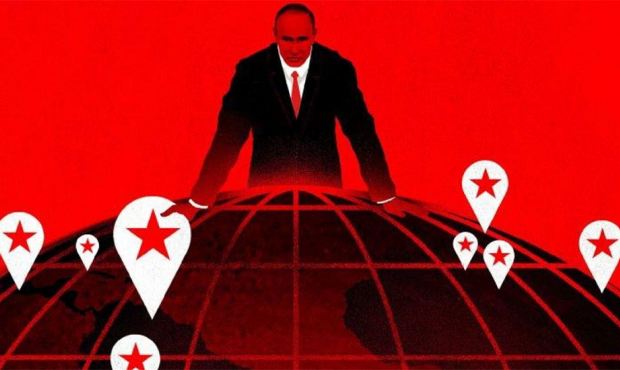

Russian Assassinations a Growing Worry as War Nears Second Year

U.S. and Ukrainian intelligence sources say Putin could call for more assassinations and asymmetric attacks on the West as war drags on

Since the outset of the war in Ukraine last February, a growing list of mysterious deaths of Vladimir Putin’s critics and Kremlin-linked foreign operations have come to light. And as the battlefield losses mount for Russian forces, there’s no question Putin is increasingly leaning on his security and intelligence services to support the war effort.

The Russian government and its foreign assassins have been linked to a brazen string of global killings in recent years, especially in Europe. U.S. and Ukrainian government sources say the Kremlin is out to settle scores, especially with dissidents and defectors. Those same sources agreed Russia could someday target some of the many foreign fighters who joined the Ukrainian war effort as reprisals when they return home.

There’s already been several stories of suspected Russian intelligence agents recently deployed abroad: An “epidemic” of suspicious oligarch deaths across the world; a letter bombing campaign against politicians in Spain thought to be backed by Russian agents; a foiled attempted-murder of a dissident Kremlin critic in France last fall; Russian military spies (GRU) in Poland active on the Ukrainian border posing as a tourist company; Bulgaria and Czechia both expelling Kremlin diplomats over the alleged bombing of ammo dumps inside their countries; and a flipped German double agent working for the Kremlin, among other incidents of Moscow-directed espionage activities.

One U.S. intelligence source familiar with Russia’s spy capabilities—who was not authorized to speak to the media—said the “reach” of their operations is vast and global. The source also noted that Russian-aligned entities with the capacity to undertake lethal operations are thought to be present on U.S. soil. The same source did temper those fears, saying a stateside Kremlin-sanctioned hit on a dissident or an American would be an escalatory and bold move. According to them, while Russia’s foreign intelligence arm (the SVR) likely doesn’t “have the bandwidth right now” for planning an “elaborate and complicated covert action” in the U.S. (something VICE News also heard from an expert on Russian intelligence), past plots in the U.K. and Germany shows they do have the appetite for operations in Europe writ-large.

“The Skripals, the Litvinenkos” they said, referring to past assassination plots in England targeting two ex-spies unfriendly to Putin (not to mention a spy-thriller level kill in Berlin of a Chechen defector in 2019) as evidence the Russian memory of its enemies is long and its willingness to send assassins to unfriendly territory is unquestionable.

The U.S. government alleges the tentacles of Russia abroad have also extended outside of official government networks.

Two weeks ago the DOJ indicted members of the broader Russian mafia known as the “Vory v Zakone” (and some of its Brooklyn-based members) or as it is referred to in court documents, the translated “Thieves-in-Law”—which the Kremlin is increasingly using as an arm of its intelligence apparatus. According to federal prosecutors, the Iranian regime hired the criminal syndicate to kill dissident journalist Masih Alinejad who is living in New York. The DOJ added that it is noticing a rise in government sponsored assassinations emanating from belligerent regimes abroad, including Russia.

“We face an alarming rise in plots emanating from Iran, China, Russia, and elsewhere, targeting people in the United States, often using criminal proxies and cutouts,” the agency said in a news release. (The DOJ and the CIA declined to further comment on Kremlin-linked covert actions in the U.S. and abroad.)

Using asymmetric methods like sabotage or assassinations to cause chaos or insecurity for its enemies is something Colin P. Clarke, director of research at intelligence consultancy firm the Soufan Group, thinks Russia is already adept at doing. Clarke sees the persistent sabre-rattling from the Kremlin for nuclear war as a smokescreen for what it is doing in the shadows.

“Common sense tells you, that's not what they're going to escalate to because we've got nukes, too,” he said. “But there's going to be steps that happen before that—that's tit for tat.

“And so we're in the middle of that game.”

Clarke has observed that Russian networks and Wagner Group—a Kremlin-allied private military contractor with thousands of mercenaries working all over the world and in Ukraine—are already asking followers on Telegram to undertake attacks on Western targets, specifically in Europe.

“It's a logical next step,” he said “they have the infrastructure in place, they have guys that are willing to do it.”

As for the threat against returnee foreign fighters, he would not be “surprised” they could end up on Russian hit lists of the future.

According to Clarke, Russian security services can tap a vast network of foreign assets, whether “Wagner guys, GRU guys, or operatives and guys that they've trained” to carry out attacks in unfriendly countries. That could also include proxies inside the Vory v Zakone, providing Putin and his intelligence agencies with what Clarke described as “plausible deniability.”

“I think this is an ideal situation for the Russians, because they can say it's a bunch of criminals that aren't connected to them, even if they're operating as kind of an extension of the Russian state,” he said.

The official spokesperson for the Russian foreign ministry, Maria Zakharova, did not respond to multiple requests for comment on a list of her country’s alleged covert actions abroad over the last decade.

Open channels of the Russian intelligence service are doing their part to favorably amplify their capabilities. In its newly-minted public relations magazine, SVR director Sergey Naryshkin reportedly claimed the agency has operatives in the West prepared to act against the Kremlin’s enemies. And suspected Russian murder plots on U.S. soil have happened in recent memory. For example, Mikhail Lesin, once a close ally to Putin and a prominent media figure among Moscow elites, was suspiciously found dead in his D.C. hotel room in 2015 (Buzzfeed News later reported via FBI sources that he was actually bludgeoned to death the night before a scheduled meeting with the Department of Justice. The chief medical examiner for the D.C. police who investigated Lesin’s death said he died of, “blunt force injuries of the neck, torso, upper extremities and lower extremities.” The U.S. government has never officially attributed his death to a murder.)

Ukrainian intelligence is well aware of the brutality of Russian death squads and the lists of people they’re known to compile against their adversaries. As Russia advanced into Ukraine, VICE News was told of hacked lists of Ukrainian servicemen and their personal data being used to aid in disappearing men in occupied regions to discourage potential insurgencies. (In retaliation, Ukraine is believed to be busy assassinating Russians like the daughter of a man nicknamed “Putin’s Rasputin” or the recent suspicious killing of a Kremlin-activist and soldier who showed off the skull of a Ukrainian defender of Azovstal.) One source in a secretive section of the Ukrainian security services confirmed Russia has continued its covert actions and assassination efforts across the board, targeting its defectors as discouragement to potential turncoats. The same source said going after returned foreign fighters is something they could see Russia doing in the future to potentially “break the will of foreign people,” joining the Ukrainian cause, but noted there has been a marked decline in their numbers of late.

They’re not all-powerful. Their security services are robust, but not everywhere

Directing operatives towards those volunteer soldiers (not unlike the way Alinejad was allegedly targeted by mafia killers), whether in Canada, Europe, or in the U.S.—places where Russian entities are known to operate—is possible, given the openness and social media exposure some of these volunteers have received. Among the cohort of western fighters who’ve publicly joined Ukrainian forces is a member of the Kennedy family, a celebrity ex-CIA media figure, and numerous Twitter accounts with hundreds of thousands of followers who’ve enjoyed widespread online support. (However, several other foreign fighters who have spoken to VICE News in the past, have requested anonymity, because of being on “Russian kill lists,” as one put it.)

During the early parts of the invasion when the first waves of foreign fighters streamed into Ukraine, a member of the American special forces community told VICE News they were stunned at their lack of operational security (posting Instagram images or tweeting personal details, for example). The source said there are “Russians all throughout the U.S.” with connections to the Kremlin who would be willingly activated against returned foreign fighters in retribution.

But Chris Chivvis, who is a former U.S. national intelligence officer in Europe and a current director of the American Statecraft Program at the Carnegie Endowment, said it is important not to overstate the power of Russian operations abroad and fall into “conspiracy theory” about their capabilities.

“They’re not all-powerful. Their security services are robust, but not everywhere,” he told VICE News in an interview. Chivvis rates Russia’s counterintelligence threat among the top adversaries to the U.S. government, but warned against exaggerating their abilities or intent for lethal operations abroad.

“What's important is to understand there are real Russian intelligence activities going on, especially in Europe, to a lesser degree, but also in the United States and certainly around the world,” said Chivvis, adding that they “do not have the reach that some people imagine they do.”

While the SVR and other Kremlin agencies have exhibited a propensity to “settle scores” with its perceived enemies overseas and outside Russia’s borders, Chivvis was clear that we should not “paint them as something more threatening than they actually are, and start to see them around every corner, because that would just not be accurate.”

One point of comfort for any future Russian attacks abroad, writ-large, is evidence of some of the spectacular failures of Russian intelligence operations to kill some of its targets in the past. Case and point, the summer of 2020 attempted murder of Alexei Navalny, largely considered the biggest political challenger to Putin’s leadership in Russia, was so botched by government assassins one of them was duped into admitting to it in a phony call from Navalny himself—and that plot all unfolded within the borders of Russia, let alone in a country unfriendly to the Kremlin and its agents. Then in September last year, assassins shot at dissident journalist Vladimir Osechkin, who publishes Gulagu.Net (which exposes Kremlin misdeeds), in his home in Biarritz, France where he was given asylum, but failed to kill him. Osechkin had been told through sources that a criminal hitman contracted by Russian security services was trying to kill him.

By Ben Makuch / VICE.COM